History

The Survey of California Indian Languages was set up informally in 1949, and on January 1, 1953 it was formally established with a permanent budget. Our research partly continues the earlier linguistic work of the Archaeological and Ethnographic Survey of California, established by A. L. Kroeber in 1901. The modern Survey’s name was eventually changed—it is now the Survey of California and Other Indian Languages—to reflect the reality that our work, though traditionally focused on California, has always also had a broader scope.

Earlier language documentation at Berkeley

A Department of Linguistics was created at the University of California in 1901, a few months before the Department of Anthropology. In both departments, the work of A. L. Kroeber, Pliny Earle Goddard, and their colleagues and students laid the foundations of our modern understanding of California’s rich linguistic texture. At the beginning of the twentieth century, scholars knew relatively little about Native people of California or their languages. Early goals thus included identifying and mapping the state’s languages, documenting traditional speech genres (such as myths and ritual language), and assessing the likely relationships among languages. Two kinds of project were especially important: dialect surveys, recording information from a variety of locations in the area of a language (this became much more difficult later when the number of speakers of any California language had been greatly reduced); and texts recorded from elderly people who had grown up without English (and often still spoke little English). This period also saw the last documentation of some of the languages most adversely affected by Spanish and English, for example on the south and central California coast.

The 1950s, 1960s & 1970s

During this period, Americanist linguistic work at Berkeley focused mainly on documentation, especially of the many poorly described languages of California, and on areal and historical analysis. The leading figure was Mary Haas, the first Director of the Survey. A student of Edward Sapir’s at the University of Chicago and then Yale, Haas came to Berkeley in 1943 and secured a regular academic position beginning in 1946. From then until her retirement in 1978 (and afterwards), as her student Karl Teeter put it, “she trained more Americanist linguists than did Boas and Sapir put together.”

Guided by Haas and by her colleague and eventual successor as Survey Director, Wallace Chafe, Berkeley dissertations in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s include over 40 grammatical descriptions and dictionaries of American Indian languages.

The areal and historical questions of interest to many Californianists in this period concerned genealogical relationships and language contact. As a result of new documentation sponsored by the Survey, a previously conjectural relationship between Algonquian languages and the northwest California languages Wiyot and Yurok was proven to the satisfaction of linguists, and the (still controversial) connections among the Hokan and the Penutian languages of California were intensively scrutinized. The formation of language areas through long-term language contact and linguistic diffusion was explored for several areas of the state, notably by Haas herself in well-known 1967 and 1970 studies of northern California.

The 1980s, 1990s & 2000s

In recent decades, language documentation has continued as one of our core missions, most recently with the support of the Robert L. Oswalt Graduate Student Support Endowment for Endangered Language Documentation. But we have also paid more attention to research projects involving language typology and linguistic theory, and throughout our work to the interests of speaker and heritage communities. We have also sponsored more work on languages outside California, especially in Latin America.

The research shift toward typological and theoretical questions reflects the growth of linguistics and the difficulty of addressing every question of linguistic interest (from phonetics, through phonology and morphology, to syntax and semantics) in one research project. From Leonard Talmy’s pathbreaking 1972 dissertation on Atsugewi semantics to four 2008 and 2009 theses focusing on phonetics and phonology, or phonology and morphology, in individual languages of Mexico, student work in recent decades has more often investigated specific linguistic topics in greater depth. At the same time, the increasing number of languages with no speakers, or speakers who only rarely use their languages, has led to extensive student work on twentieth-century language change, language revitalization, or languages mainly accessible through archival materials. In at least two cases—Marc Okrand’s dissertation on Mutsun (1977), and David Costa’s on Miami-Illinois (1994)—this kind of archival work has led directly to active language revitalization programs.

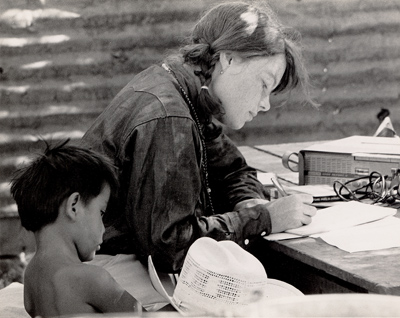

Under the leadership of Leanne Hinton, the third Survey Director, we have been engaged in active outreach to California Indian communities. This includes workshops (on documentation, revitalization, and language learning) for communities through the state, visits to our archive, and the biennial Breath of Life Archival Institute, a workshop for California Indians whose languages have few or no remaining native speakers.

The 2010s & 2020s

Most recently, we have come to participate more actively in a growing worldwide movement of digital language archives such as the Archive of the Indigenous Languages of Latin America (AILLA), the Endangered Languages Archive (ELAR), and the Pacific and Regional Archive for Digital Sources in Endangered Cultures (PARADISEC), becoming a member of the Digital Endangered Languages and Musics Archives Network (DELAMAN). In that context, we have focused on digital repatriation: scanning and digitizing legacy materials, and making them accessible through our newer digital catalog, which facilitates distant access to cultural and linguistic heritage materials. The catalog also includes Indigenous language sound recordings (from as early as 1901) held by the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology. As of October 2021, the California Language Archive — the newer name for the repository in the larger Survey research center — lists over 16,000 items (including some 3,500 physical items) on over 490 languages, with over 43,000 digital files (excluding those held by the Hearst Museum).

We have also renewed efforts in the acquisition of archival materials, both at-risk analog materials held in private hands, and born-digital materials that stem from recent and ongoing language documentation and revitalization projects. In this context, the scope of our acquisitions has expanded to include any Indigenous language from the Americas, as well as any studied by Berkeley linguists. The California Language Archive now maintains a “pre-archive,” a digital interface used directly by depositors to create catalog items and associated metadata and to upload digital files for new collections. Recent projects involving Berkeley linguists have significantly expanded our holdings of African and Latin American Indigenous languages materials in particular. For example, the eight Americanist dissertations since 2018 have focused on languages of Latin America.

Looking to the future

For over 100 years, the academic study of California languages and linguistics has been dominated by the concern among scholars that the diversity and richness of our state’s languages are in danger of vanishing. Already in April 1901, A. L. Kroeber’s teacher Franz Boas wrote to urge the establishment of anthropological and language documentation programs at Berkeley. Boas emphasized “that it is only a question of a very few years when [California Indian] languages…will have disappeared.” The urgency was real; half of California’s languages have no native speakers today. But it is important to add that California’s Native people and languages are resilient and adaptive; that languages are being learned, transformed, and revived in the face of tremendous obstacles; and that so far, every generation of scholars has been wrong in its prediction that California languages are on the verge of extinction.