Collection spotlight

Anna Lewington Collection of Matsigenka and Yine Recordings

No archival collection is too small! Our first collection accessioned this year was the Colección de grabaciones en matsigenka y yine de Anna Lewington (Lewington 2022+). It consists of digitized, edited sound recordings from two cassettes made by Anna Lewington in the Urubamba River valley, in the Peruvian Amazon, in November and December 1981. Ms. Lewington’s research at this time formed the basis of her master’s thesis at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland (Lewington 1985). She graciously donated the recordings, which she had digitized and edited in England, after I emailed her in May 2021 asking whether she was in possession of documentary materials from her fieldwork. I was familiar with Ms. Lewington’s work in the context of my work with speakers of Caquinte (O’Hagan 2020). Caquinte is related most closely to Matsigenka (Snell 2011; see Mihas 2017 for subfamily), and more distantly to Yine; all three belong to the Arawak language family, one of the most widespread in the Americas (see Aikhenvald 1999). All three languages are vital, but people who speak them live in regions undergoing rapid socioeconomic and cultural changes that make the documentation of these genres — and the preservation of existing documentation — critical. Because Ms. Lewington is not a linguist, the preservation of her recordings is especially critical for the accurate representation of the voices of the speakers of Matsigenka and Yine that collaborated with her. I give specific examples of this in this post. My aim is not to criticize Ms. Lewington’s thesis, but simply to show what more can be learned from these archival materials.

The recordings were made in the Yine community of Miaría and in the Matsigenka communities of Nueva Luz, Chokoriari, and Timpia. They feature the voices of at least 14 Matsigenka and Yine people (whose voices, to my knowledge, have not been recorded elsewhere), and include stories, songs, and flute and drum music. Ms. Lewington was interested in different versions of the traditional story of the origin of manioc, a staple food in many Amazonian societies. (Indeed in Matsigenka the word for ‘manioc,’ sekatsi, is polysemous: it also means ‘food.’ The verb root seka also means ‘eat.’) While her representations of Matsigenka words are on the right track, there are many errors related to word boundaries, the segmentation of verbal affixes, and, understandably, translation, among others. As she herself describes her process in her thesis (Lewington 1985:83-84):

The most useful aid to this work [transcription and translation] was the volume of Machiguenga [sic] myths recorded by Dr [Gerhard] Baer, a number of which were made available to me in the original Machiguenga with their German and/or Spanish translations. Amongst these was Baer's version of the manioc myth, referred to by Baer as 'Mythe vom Mond' (1984: 423). A careful study of the linguistic structuring presented by this myth in particular and a process of cross-checking to identify form and meaning, enabled me to transcribe and translate a good deal of my own myth version.

Circumstances beyond my control unfortunately prevented me from either transcribing or translating the myth in the field. Both tasks were therefore undertaken in England.

The translation of the Machiguenga text is regrettably incomplete. This is due to my own unfamiliarity with the language itself and the inevitable problems presented by the lack of a reliable grammar or vocabulary from Machiguenga into any other language.

Though I have attempted to follow Baer's (1984: 52) notes, and the observations of Snell (1978), the transcription and subsequent translation of the myth are not necessarily accurate or, with regard to the Machiguenga language, consistent phonemically.

It is stressed that the analytical work was undertaken without the help of a Machiguenga informant (to whom it was impossible to return at the end of my first field trip), thus the thesis is concerned not to present an article of linguistic perfection, but rather to present the evidence of the myth itself, the lore surrounding manioc and all that this represents to the Machiguenga.

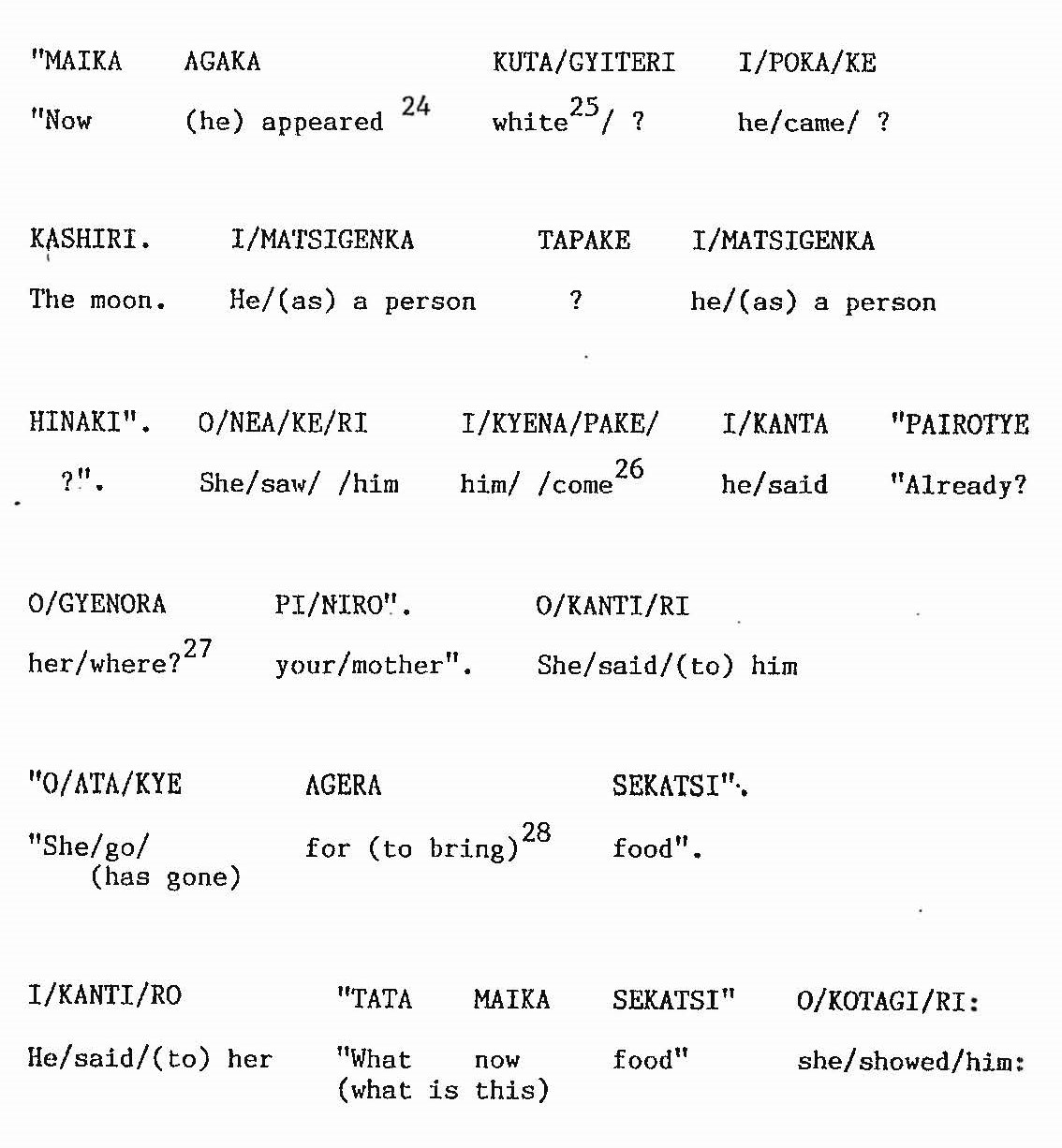

As a result, the original recordings are critical for the accurate transcription (and translation, of course) of the texts Ms. Lewington recorded. In what follows, I show how the transcription and translation can be improved, using the example of an excerpt from Bartolomé Ríos Corral’s “The Manioc Myth,” recorded on November 28, 1981 in Nueva Luz (catalogue item 2022-01.003). First, listen to the excerpt, following along with Ms. Lewington’s transcription and translation below (ibid.:95-96).

A full transcription and translation are given below. Relisten to the excerpt, following along here.

Agaka kutagiteri ipokake kashiri. Imatsigenkatapaake, matsigenka inake. Oneakeri, ikenapaake, ikantapairo, "Tyara okenanake piniro?" Okantiri, "Atake age sekatsi." Ikantiro, "Tyati maika sekatsi?" Okotagiri, "Nero oka." Ikanti, "Oka tera iro sekatsi, onti kipatsi, pogavagetakara onti kipatsi."

One day, Moon came. Upon arrival, he transformed into a person, he was a person. She saw him, he came, and he said to her, "Where did your mother go?" She said to him, "She's gone to get food." He said to her, "What now is food?" She showed him, "Here it is." He said, "This isn't food, it's dirt, when you've been eating it's dirt."

Now I segment the seven sentences comprising this excerpt, providing interlinear glosses. I discuss sentence by sentence how this analysis differs from Ms. Lewington’s nascent one, noting a handful of differences and leaving some for the reader to notice. In this part of the story, a young Matsigenka girl who has been confined to her menarche seclusion hut is visited by Moon. Up to this point, the girl believes the substance her mother has been bringing her for sustenance is food, but in fact it’s dirt (because humans do not yet have real food), a fact that Moon reveals to the girl. (Note AR = active realis; MR = middle realis. These suffixes express both voice and reality status. See Michael 2014 for the category of reality status in this branch of Arawak. AL = alienator, a suffix that allows inalienable nouns to occur without a possessor.)

1. Agaka kutagiteri ipokake kashiri.

ag-ak-a-ø kutagiteri i-pok-ak-i kashiri

arrive(.day)-PFV-MR-3 day 3M-come-PFV-AR moon

One day, Moon came.

The word for ‘day’ is kutagiteri, a lexicalized stem based on the stative verb kuta ‘be white,’ -gite, a classifier for nouns referring to spaces in the natural world (e.g., forest, sky), and the nominalizer -ri (cf. Ms. Lewington’s “KUTA/GYITERI”). The middle verb ag ‘arrive,’ said of days, is productive, but the collocation agaka kutagiteri is a relatively fixed expression, akin to English one day. In the remainder of the sentence, we find another verb phrase with the same verb-subject order. Ms. Lewington misidentifies the root as /poka/ ‘come’ (cf. “I/POKA/KE”); the perfective and voice-reality status suffixes follow.

2. Imatsigenkatapaake, matsigenka inake.

i-matsigenka-t-apa-ak-i matsigenka i-n-ak-i

3M-person-EP-ALL-PFV-AR person 3M-be-PFV-AR

Upon arrival, he transformed into a person, he was a person.

In (2), there are two verb phrases describing the Moon’s transformation into a person. The first zero-verbalizes the noun matsigenka ‘person’ (n.b., the ‘upon arrival’ translation comes from allative -apa); the second involves the same noun followed by the copular verb n ‘be’ (cf. nti below). In addition, in this example we also encounter epenthesis for the first time: underlying vowel sequences are broken up by -t; underlying consonant sequences are broken up by -a (the latter not shown here). There is no epenthesis between the allative and the perfective because the allative historically ended in /h/ (cf. Caquinte -(a)poj). In contrast, Ms. Lewington does not recognize the verbalized matsigenka as a single word (nor the vowel length at the boundary of the allative and perfective), nor does she identify the copula.

3. Oneakeri, ikenapaake, ikantapairo, “Tyara okenanake piniro?”

o-ne-ak-i-ri i-ken-apa-ak-i i-kant-apa-i-ro

3F-see-PFV-AR-3M 3M-go-PFV-AR 3M-say-ALL-AR-3F

tya=ra o-ken-an-ak-i pi-niro

WH=SUB 3F-go-ABL-PFV-AR 2-mother

She saw him, he came, and he said to her, “Where did your mother go?”

In (3), there are three relatively straightforward verbal words preceding the quote, the second two marked with allative -apa. The verb ken ‘go’ warrants mention, its gloss being somewhat misleading: with -apa it means ‘come,’ but with ablative -an, as occurs in the quote, it means ‘go’; it means to follow a particular route. Ms. Lewington did not recognize that ken appears twice in this sentence. In addition, she continues as in (2) to include vowels as parts of roots (i.e., “O/NEA/KE/RI” and “I/KYENA/PAKE/”) that in fact belong to the following suffixes (in addition to other morpheme boundary errors, as with the perfective and reality status suffixes), and there are errors in word boundaries. Notably, the “PAIROTYE” she glosses as ‘already’ consists of material belonging to the preceding verb in addition to a following interrogative pronoun tya.

4. Okantiri, “Atake age sekatsi.”

o-kant-i-ri a-t-ak-i-ø o-ag-e seka-tsi

3F-say-AR-3M go-EP-PFV-AR-3 3F-get-IRR food-AL

She said to him, “She’s gone to get food.”

The principal new kind of error in (4) concerns adding a prefix to atake that is in fact absent; instead the third person feminine subject is expressed by a suffix. This is part of a pattern of split marking of subjects found in many Arawak languages (see O’Hagan 2021 for comparison with Caquinte).

5. Ikantiro, “Tyati maika sekatsi?”

i-kant-i-ro tya-ti maika seka-tsi

3M-say-AR-3F WH-INAN now food -AL

He said to her, “What now is food?”

In (5), we observe a new kind of segmentation error, including active realis -i as part of the verb root kant ‘say.’ Moreover, Ms. Lewington misidentifies the interrogative pronoun as tata instead of tyati, which is inflected for animacy (see animate -ni vs. inanimate -ti). Note by now the double entendre, as it were, of sekatsi ‘food, manioc.’

6. Okotagiri, “Nero oka.”

o-okotag-i-ri ne-ro o-ka

3F-show-AR-3M PRES-F 3F-PROX

She showed him, “Here it is.”

Example (6) shows the same segmentation error involving -i, and for the first time Ms. Lewington misidentifies a prefix-root boundary. The verb root is in fact okotag, with an initial /o/. In these cases, third person feminine is expressed by the null allomorph ø-. Then, what goes unsegmented as “NEROK” is in fact two words: the presentative particle ne, which inflects for the gender of its complement, and the proximal demonstrative ka, which also inflects (differently) for gender.

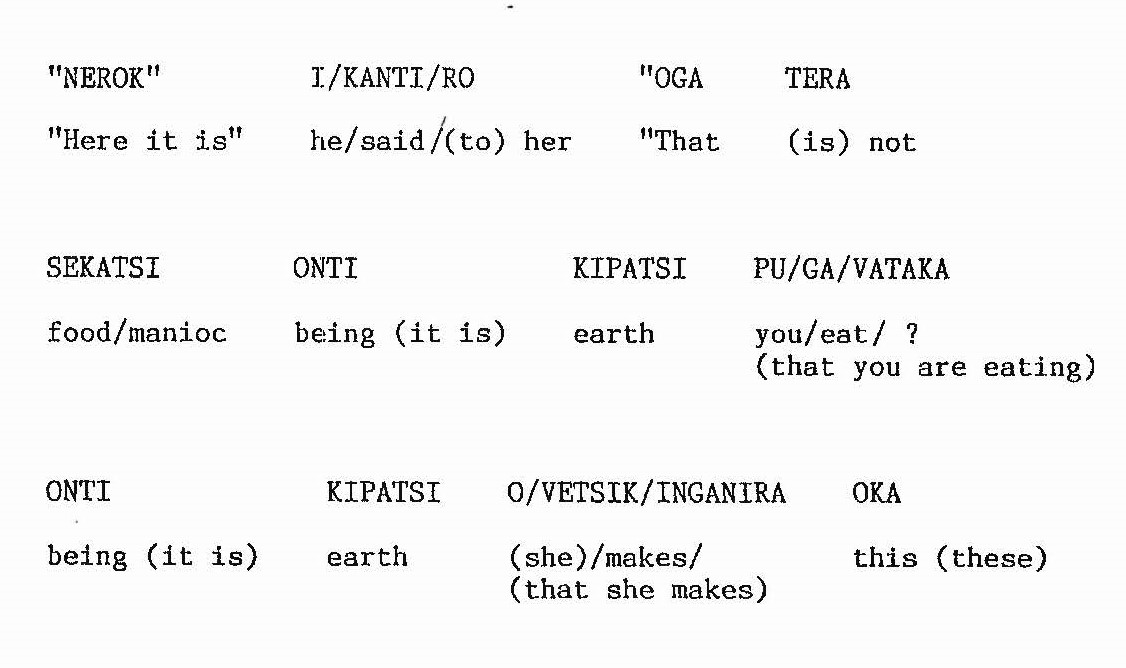

7. Ikanti, “Oka tera iro sekatsi, onti kipatsi, pogavagetakara onti kipatsi.”

i-kant-i o-ka tera iro seka-tsi o-nti kipatsi

3M-say-AR 3F-PROX NEG 3F.PRO food-AL 3F-COP dirt

pi-og-a-vage-t-ak-a=ra o-nti kipatsi

2-eat-EP-DUR-EP-PFV-MR=SUB 3F-COP dirt

He said, “This isn’t food, it’s dirt, when you’ve been eating it’s dirt.”

Example (7) shows multiple nonverbal clauses, first a negated one, consisting of a topicalized oka ‘this,’ followed by the third person feminine focus pronoun iro and the predicate, which is negated. The correction involves the positive polarity defective copula nti, which inflects only for a subject. (See O’Hagan 2020:33-48 for parallel forms in Caquinte.) The verb includes what is known in studies of these languages as the durative -vage, here expressing that the addressee has been eating dirt for a long time.

The California Language Archive recently received a larger donation from anthropologist Allen Johnson, Professor Emeritus of Anthropology at UCLA, of field notes, sound recordings, films, and photographs from his fieldwork in Matsigenka communities in the Urubamba valley, especially in Shimaa, so stay tuned for more archival materials related to Matsigenka!

References

- Aikhenvald, Alexandra Y. 1999. The Arawak Language Family. In The Amazonian Languages, ed. R.M.W. Dixon and Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, 65-106. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Baer, Gerhard. 1984. Die Religion der Matsigenka, Ost-Peru. Basel: Wepf.

- Lewington, Anna. 1985. The Implications of Manioc Cultivation in the Culture and Mythology of the Machiguenga of South Eastern Peru. MA thesis, University of St. Andrews.

- Lewington, Anna. 2022+. Colección de grabaciones en matsigenka y yine de Anna Lewington, 2022-01, California Language Archive, Survey of California and Other Indian Languages, University of California, Berkeley. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.7297/X2542MB5.

- Michael, Lev. 2014. The Nanti Reality Status System: Implications for the Typological Validity of the Realis/Irrealis Contrast. Linguistic Typology 18(2):251-288. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/lingty-2014-0011.

- Mihas, Elena. 2017. The Kampa Subgroup of the Arawak Language Family. In The Cambridge Handbook of Linguistic Typology, ed. Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald and R.M.W. Dixon, 782-814. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316135716.025.

- O’Hagan, Zachary. 2020. Focus in Caquinte. PhD dissertation, University of California, Berkeley. URL: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9640m1fg.

- O’Hagan, Zachary. 2021. Split Subject Marking in Caquinte. Berkeley: Talk at Syntax and Semantics Circle, December 3. URL: https://linguistics.berkeley.edu/~zjohagan/pdflinks/ohagan_cot_sscircle_subject-marking_v1.pdf.

- Snell, Betty A. 1978[1974]. Machiguenga: Fonología y vocabulario breve. Yarinacocha: SIL.

- Snell, Betty A. 2011. Diccionario matsigenka-castellano con índice castellano, notas enciclopédicas y apuntes gramaticales. Lima: SIL.